Introduction to Objects

It’s time to learn more about the basic structure that permeates nearly every aspect of JavaScript programming: objects.

You’re probably already more comfortable with objects than you think, because JavaScript loves objects! Many components of the language are actually objects under the hood, and even the parts that aren’t— like strings or numbers— can still act like objects in some instances.

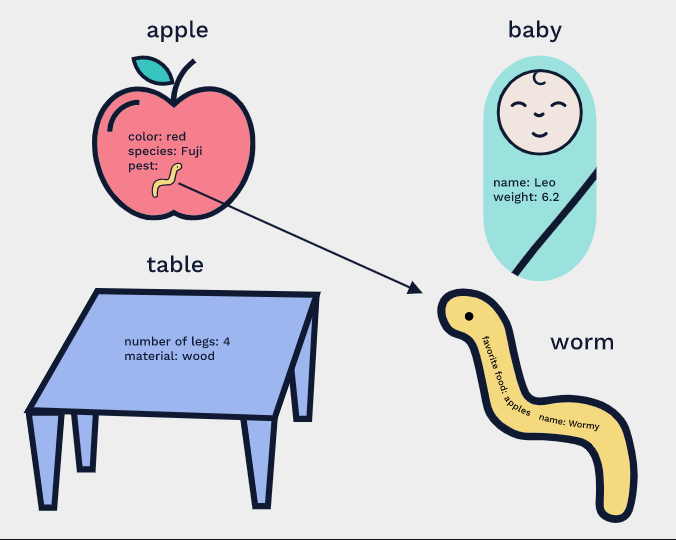

There are only seven fundamental data types in JavaScript, and six of those are the primitive data types: string, number, boolean, null, undefined, and symbol. With the seventh type, objects, we open our code to more complex possibilities. We can use JavaScript objects to model real-world things, like a basketball, or we can use objects to build the data structures that make the web possible.

At their core, JavaScript objects are containers storing related data and functionality, but that deceptively simple task is extremely powerful in practice. You’ve been using the power of objects all along, but now it’s time to understand the mechanics of objects and start making your own!

Objects can be assigned to variables just like any JavaScript type. We use curly braces, {}, to designate an object literal:

We fill an object with unordered data. This data is organized into key-value pairs. A key is like a variable name that points to a location in memory that holds a value.

A key’s value can be of any data type in the language including functions or other objects.

We make a key-value pair by writing the key’s name, or identifier, followed by a colon and then the value. We separate each key-value pair in an object literal with a comma (,). Keys are strings, but when we have a key that does not have any special characters in it, JavaScript allows us to omit the quotation marks:

let spaceship = {

'Fuel Type': 'diesel',

color: 'silver'

};

The spaceship object has two properties Fuel Type and color. 'Fuel Type' has quotation marks because it contains a space character.

Let’s make some objects!

There are two ways we can access an object’s property. Let’s explore the first way— dot notation, ..

You’ve used dot notation to access the properties and methods of built-in objects and data instances:

With property dot notation, we write the object’s name, followed by the dot operator and then the property name (key):

homePlanet: 'Earth',

color: 'silver'

};

spaceship.homePlanet; // Returns 'Earth',

spaceship.color; // Returns 'silver',

If we try to access a property that does not exist on that object, undefined will be returned.

Let’s get some more practice using dot notation on an object!

The second way to access a key’s value is by using bracket notation, [ ].

You’ve used bracket notation when indexing an array:

To use bracket notation to access an object’s property, we pass in the property name (key) as a string.

We must use bracket notation when accessing keys that have numbers, spaces, or special characters in them. Without bracket notation in these situations, our code would throw an error.

'Fuel Type': 'Turbo Fuel',

'Active Duty': true,

homePlanet: 'Earth',

numCrew: 5

};

spaceship['Active Duty']; // Returns true

spaceship['Fuel Type']; // Returns 'Turbo Fuel'

spaceship['numCrew']; // Returns 5

spaceship['!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!']; // Returns undefined

With bracket notation you can also use a variable inside the brackets to select the keys of an object. This can be especially helpful when working with functions:

returnAnyProp(spaceship, 'homePlanet'); // Returns 'Earth'

If we tried to write our returnAnyProp() function with dot notation (objectName.propName) the computer would look for a key of 'propName' on our object and not the value of the propName parameter.

Let’s get some practice using bracket notation to access properties!

Once we’ve defined an object, we’re not stuck with all the properties we wrote. Objects are mutable meaning we can update them after we create them!

We can use either dot notation, ., or bracket notation, [], and the assignment operator, = to add new key-value pairs to an object or change an existing property.

One of two things can happen with property assignment:

- If the property already exists on the object, whatever value it held before will be replaced with the newly assigned value.

- If there was no property with that name, a new property will be added to the object.

It’s important to know that although we can’t reassign an object declared with const, we can still mutate it, meaning we can add new properties and change the properties that are there.

spaceship = {type: 'alien'}; // TypeError: Assignment to constant variable.

spaceship.type = 'alien'; // Changes the value of the type property

spaceship.speed = 'Mach 5'; // Creates a new key of 'speed' with a value of 'Mach 5'

You can delete a property from an object with the delete operator.

'Fuel Type': 'Turbo Fuel',

homePlanet: 'Earth',

mission: 'Explore the universe'

};

delete spaceship.mission; // Removes the mission property

When the data stored on an object is a function we call that a method. A property is what an object has, while a method is what an object does.

Do object methods seem familiar? That’s because you’ve been using them all along! For example console is a global javascript object and .log() is a method on that object. Math is also a global javascript object and .floor() is a method on it.

We can include methods in our object literals by creating ordinary, comma-separated key-value pairs. The key serves as our method’s name, while the value is an anonymous function expression.

invade: function () {

console.log('Hello! We have come to dominate your planet. Instead of Earth, it shall be called New Xaculon.')

}

};

With the new method syntax introduced in ES6 we can omit the colon and the function keyword.

invade () {

console.log('Hello! We have come to dominate your planet. Instead of Earth, it shall be called New Xaculon.')

}

};

Object methods are invoked by appending the object’s name with the dot operator followed by the method name and parentheses:

In application code, objects are often nested— an object might have another object as a property which in turn could have a property that’s an array of even more objects!

In our spaceship object, we want a crew object. This will contain all the crew members who do important work on the craft. Each of those crew members are objects themselves. They have properties like name, and degree, and they each have unique methods based on their roles. We can also nest other objects in the spaceship such as a telescope or nest details about the spaceship’s computers inside a parent nanoelectronics object.

telescope: {

yearBuilt: 2018,

model: '91031-XLT',

focalLength: 2032

},

crew: {

captain: {

name: 'Sandra',

degree: 'Computer Engineering',

encourageTeam() { console.log('We got this!') }

}

},

engine: {

model: 'Nimbus2000'

},

nanoelectronics: {

computer: {

terabytes: 100,

monitors: 'HD'

},

'back-up': {

battery: 'Lithium',

terabytes: 50

}

}

};

We can chain operators to access nested properties. We’ll have to pay attention to which operator makes sense to use in each layer. It can be helpful to pretend you are the computer and evaluate each expression from left to right so that each operation starts to feel a little more manageable.

In the preceding code:

- First the computer evaluates

spaceship.nanoelectronics, which results in an object containing theback-upandcomputerobjects. - We accessed the

back-upobject by appending['back-up']. - The

back-upobject has abatteryproperty, accessed with.batterywhich returned the value stored there:'Lithium'

Objects are passed by reference. This means when we pass a variable assigned to an object into a function as an argument, the computer interprets the parameter name as pointing to the space in memory holding that object. As a result, functions which change object properties actually mutate the object permanently (even when the object is assigned to a const variable).

homePlanet : 'Earth',

color : 'silver'

};

let paintIt = obj => {

obj.color = 'glorious gold'

};

paintIt(spaceship);

spaceship.color // Returns 'glorious gold'

Our function paintIt() permanently changed the color of our spaceship object. However, reassignment of the spaceship variable wouldn’t work in the same way:

homePlanet : 'Earth',

color : 'red'

};

let tryReassignment = obj => {

obj = {

identified : false,

'transport type' : 'flying'

}

console.log(obj) // Prints {'identified': false, 'transport type': 'flying'}

};

tryReassignment(spaceship) // The attempt at reassignment does not work.

spaceship // Still returns {homePlanet : 'Earth', color : 'red'};

spaceship = {

identified : false,

'transport type': 'flying'

}; // Regular reassignment still works.

Let’s look at what happened in the code example:

- We declared this

spaceshipobject withlet. This allowed us to reassign it to a new object withidentifiedand'transport type'properties with no problems. - When we tried the same thing using a function designed to reassign the object passed into it, the reassignment didn’t stick (even though calling

console.log()on the object produced the expected result). - When we passed

spaceshipinto that function,objbecame a reference to the memory location of thespaceshipobject, but not to thespaceshipvariable. This is because theobjparameter of thetryReassignment()function is a variable in its own right. The body oftryReassignment()has no knowledge of thespaceshipvariable at all! - When we did the reassignment in the body of

tryReassignment(), theobjvariable came to refer to the memory location of the object{'identified' : false, 'transport type' : 'flying'}, while thespaceshipvariable was completely unchanged from its earlier value.

Loops are programming tools that repeat a block of code until a condition is met. We learned how to iterate through arrays using their numerical indexing, but the key-value pairs in objects aren’t ordered! JavaScript has given us alternative solution for iterating through objects with the for...in syntax .

for...in will execute a given block of code for each property in an object.

crew: {

captain: {

name: 'Lily',

degree: 'Computer Engineering',

cheerTeam() { console.log('You got this!') }

},

'chief officer': {

name: 'Dan',

degree: 'Aerospace Engineering',

agree() { console.log('I agree, captain!') }

},

medic: {

name: 'Clementine',

degree: 'Physics',

announce() { console.log(`Jets on!`) } },

translator: {

name: 'Shauna',

degree: 'Conservation Science',

powerFuel() { console.log('The tank is full!') }

}

}

};

// for...in

for (let crewMember in spaceship.crew) {

console.log(`${crewMember}: ${spaceship.crew[crewMember].name}`);

}

Our for...in will iterate through each element of the spaceship.crew object. In each iteration, the variable crewMember is set to one of spaceship.crew‘s keys, enabling us to log a list of crew members’ role and name.

Way to go! You’re well on your way to understanding the mechanics of objects in JavaScript. By building your own objects, you will have a better understanding of how JavaScript built-in objects work as well. You can also start imagining organizing your code into objects and modeling real world things in code.

Let’s review what we learned in this lesson:

- Objects store collections of key-value pairs.

- Each key-value pair is a property—when a property is a function it is known as a method.

- An object literal is composed of comma-separated key-value pairs surrounded by curly braces.

- You can access, add or edit a property within an object by using dot notation or bracket notation.

- We can add methods to our object literals using key-value syntax with anonymous function expressions as values or by using the new ES6 method syntax.

- We can navigate complex, nested objects by chaining operators.

- Objects are mutable—we can change their properties even when they’re declared with

const. - Objects are passed by reference— when we make changes to an object passed into a function, those changes are permanent.

- We can iterate through objects using the

For...insyntax.

![diagram showing how an object followed by brackets ([]) with the property name as a string can be reassigned to a new value. This same idea applies for accessing a property using dot notation which has the object name, followed by a dot and the name of the property](https://static-assets.codecademy.com/Courses/Learn-JavaScript/objects/object_property_assignment.svg)

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you :)